News

My encounter with Taita Querubin Queta

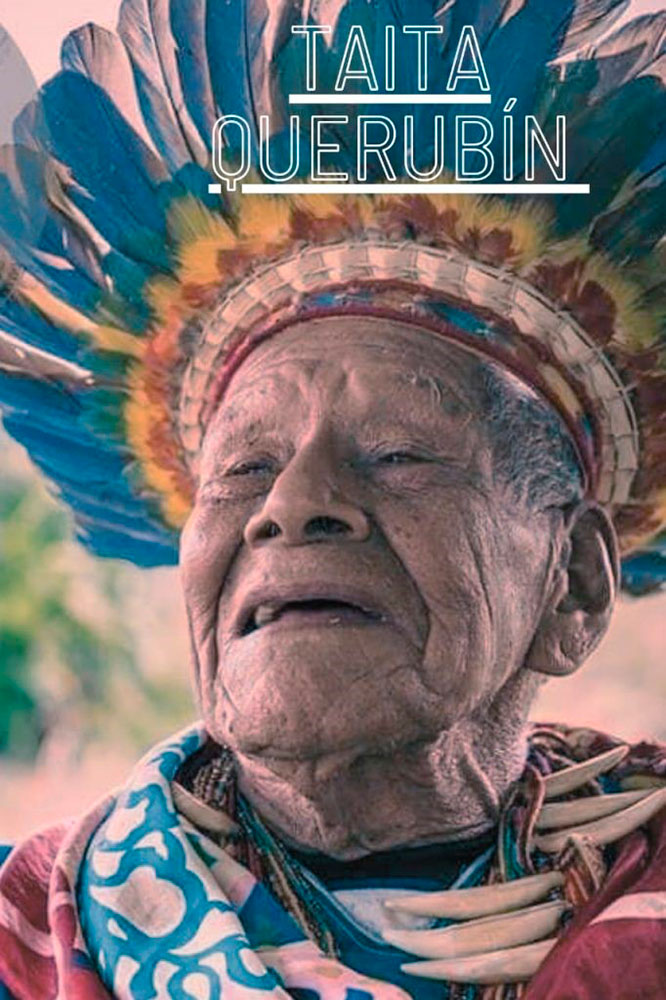

Colombian Taita Querubín Queta1 died on February 3, 2024 at the age of 110. Of the Kofan ethnic group, he has been a notable indigenous leader and prominent shaman, recognized and highly respected by his Colombian peers from different indigenous groups.

Born in 1913 in San Antonio, Guamuéz Valley, Taita Querubín Queta dedicated his entire life to preserving the traditions and ancestral wisdom of the Colombian Amazon. His death on February 3, 2024 leaves a void in the community and unanimous recognition for his contribution to the preservation of indigenous culture.

With other indigenous leaders of various ethnic groups, he has promoted the formation of the Union of Yacegeros [ayahuasqueros] Doctors of the Colombian Amazon (UMIYAC), which brought together some 9 Amazonian ethnic groups. This group, promoted from the Western medical side by our friend Dr. Germán Zuluaga, has produced a very valuable Code of Ethics that remains as a reference regarding ayahuasca intake seen from the indigenous traditional perspective.

In August 2010 (17-21), my wife Rosa Giove and I participated in the II Meeting of Indigenous Cultures in the city of Pasto, Nariño, Colombia. Rosa gave a conference on “The Human and the Cosmos” that has been highly applauded, and she participated in a meeting of Healing Women.

Organized by the Government of Nariño, the Meeting had academic interventions, cultural activities and at the same time ritual healing spaces led by various healers (ayahuasca-yagé, huachuma, peyote, yopo, temazcal, inipi...).

On this trip, I was invited to participate in the General Assembly of the UMIYAC in Mocoa, by Taita Humberto Piaguaje, of the Siona ethnic group and Senior Councilor of the UMIYAC. I was the only non-indigenous and it was a privilege to attend this meeting because of the closeness I had with Maestro Humberto. Humberto Piaguaje had come to Takiwasi three times, with his wife, where he had led ayahuasca sessions, showing great expertise and mastery of his medical art.

On this occasion he also invited me to his house in the Buena Vista Reservation, a Siona community located on the banks of the Putumayo River. In his maloca located a short distance from his house, he led an ayahuasca session for his community where about 40 people, men and women, participated. I was the only non-indigenous present. It was enlightening to watch the way they conducted the session and at the same time disconcerting compared to our usual way in Takiwasi. This ceremony was filmed, very discreetly, by a Spanish-Canadian team (Jerónimo Mazarrasa - Mark Ellam) in the context of a documentary about Takiwasi.

Women were separated from men, to one side. Throughout the ceremony, at regular intervals, a young man passed between the participants with incense to cleanse the environment. We were in hammocks, without a bucket to vomit. If necessary, one had to rush outside, the same to defecate in the clearing in the surrounding forest. Out of compassion they gave me a bucket which reassured me because I didn't know if I would reach the exit in time in case of urgent need. The preparation of yagé is with the ayahuasca vine and with “yage” (Diplopterys cabrerana) in the place of our usual chacruna (Psychotria viridis). It has slower, but more lasting effects, generally with waves of dizziness alternating with moments of rest, and with almost imperative purgative effects. The master healers or taitas sing in no particular order, sometimes simultaneously and with different ikaros. Outside the maloca a bonfire is lit. Participants move around as they please, leaving and entering as they please, giving a feeling of disorder for one accustomed to the Takiwasi style. The healers begin to carry out individual healings at midnight where they make frequent use of nettle leaves to flagellate the patient's naked body, after which they anoint him with a scented oil with very pleasant sedative effects.

Humberto was kind enough to place my hammock next to his. The sitting position on the floor in Takiwasi provides a sense of stability that allows one to “touch down” when one is very intoxicated. This time, I felt like I was on a permanent slide, with the double pleasant sensation of floating in the air and the distressing sensation of not being able to stabilize during the peaks of dizziness. A very dazed participant came to sit near my head, his face a few centimeters from mine, and he began to scream with happiness, wanting to share his joy in Spanish... Another man screamed and lay on the floor until he was rolling down the wooden stairs, the maloca being supported on sticks that kept it a little more than a meter from the ground. He ended up lying under the maloca. Humberto was unfazed by all these moves and when I suggested that this man perhaps needed help, he told me “Ayahuasca punishes him because he is a drunk, don’t worry.” In fact, the next morning he looked calm with an embarrassed face.

In the early morning, as the day dawned, I had the right to a flagellation of my torso with nettle leaves and then the soothing and welcome balm.

With all this disconcerting context for me, I could not concentrate as usual, but I saw through the skylight of the maloca, the imposing figure of a burly man with the face of a tiger and very bright eyes staring at me. I rationally realized that this image was due to the reflections of the moon in the surrounding trees, but at the same time in the symbolic dimension to which the plant gives access, I knew that it had another reality that I could not decipher. It didn't seem aggressive or with a specific intention, it was simply there, static, looking at me incessantly. I was impressed by the fact that I saw this figure remain throughout the night, at least that was my sensation, although the moon was moving.

The next day, walking back to his house, Humberto asked about my experience during the ceremony. I then told him how my session had been dominated by this enigmatic presence. He was very surprised by this, he stopped and told me in a tone that was both surprised and admired: “So, you really are an ayahuasquero.” And he explained to me that the ayahuasca that he had prepared was the “tiger-ayahuasca” and if the spirit of this ayahuasca had been seen, it was like a form of permission, of welcome into the indigenous world. I felt as if a door was opening in his mind and for me a pride like a soldier whose braids are placed on epaulets, I had risen through the ranks...

For the Colombian Amazonian indigenous people, and for Humberto as an “elder”, the yagé is theirs, their property, their inheritance. If they allow non-indigenous people to take ayahuasca, it is only as patients, but they do not conceive that its legitimate use can be transferred to non-indigenous strangers. Previously, in Takiwasi, he always took ayahuasca and he was the one who led the sessions. He was intrigued that we as Westerners could lead sessions and he didn't really take us seriously. Maybe we were well-intentioned people acting as apprentices, playing in the minor league. Once, at the end of a ceremony, as a test, he unexpectedly asked me to sing an ikaro. I didn't expect it and I felt like he was passing a test in front of the teacher. I stood up and appealed to the eldest ikaro to impress him, the “Lord of Miracles.” He gave me a good grade, “not bad,” he was surprised, but it was not enough to shake his certainty that a Westerner cannot become a Taita, perhaps just a lifelong learner. He had also noticed the order and rigor in the ayahuasca sessions in Takiwasi and he took it as a good, inspiring thing. He had even agreed to bring the women into the session circle, given that during his first sessions in Takiwasi he had placed them outside the circle, at the back of the maloca...

This time, in Buena Vista, I felt that the attention he was already showing me, the privileges to which he gave me access as a non-indigenous, were based on a kind of recognition that broke his schemes.

With this same paternal attention, from Taita to apprentice, he introduced me to the ayahuasca session with Taita Querubin Queta, in Pasto, in August 2010. A dozen other master healers of different ethnicities and about 30 other people from the Meeting participated. The Taitas formed a small circle and Humberto placed me to the right of him, a distinguished honor. The other participants formed a wider circle around them. We were in a huge room, probably a sports room, with a stove in the middle. It was very cold, Pasto is located 2500m above sea level, and it was winter. Accustomed to taking ayahuasca in tropical environments, I suffered from the cold all night and then had to move near the stove and I wrapped in all the clothes I could find.

The circle of the Taitas was impressive, the indigenous people of the Colombian Amazon wear multiple necklaces and pectoral ornaments, and especially with tiger teeth. The number of ornaments and tiger teeth symbolize their rank in the spiritual world. I met the “bishops” of different ethnicities and the “Pope” was Querubin Queta. Everyone showed him great respect and the great Humberto, the oldest elder of the Kofan, suddenly looked like a shy child, full of reverence when he talked to him.

Taita Querubin did not flaunt his rank, there was no need: at the moment of the intake, everyone knows who is who, who has strength and power. In the election of the three elders of the UMIYAC meeting in Mocoa, there was no need for electoral speeches or propaganda. Simply, the participants proposed three names, which undoubtedly prevailed when facing the onslaught of the yagé ceremonies. The assembly was asked if there was any opposition or other contrary notice. Nobody objected. Election over, the three proposed people were named “elders” of the UMIYAC. The whole process took, at most, half an hour.

Outside the ceremonial context, Querubin Queta presented himself as an affable and joking man. The previous afternoon, we all went out into town and went to look at the tourist souvenir shops. Taita Querubin was struck by a store where they sold sunglasses. And he bought some wide, dark sunglasses that made him look like a showbiz person. He laughed at the astonishment of passersby seeing this elderly indigenous man with his necklaces and Ray Charles-style sunglasses.

After drinking ayahuasca, waiting for the effects, the Taitas began to tell each other about their typically jungle adventures, where their encounters and relationship with tigers had the most space. I could follow the conversation since they used Spanish as a common language. I felt privileged and living an exceptional moment, as if in another space-time.

The dizziness that arrived did not allow me to continue following the course of the conversations. The Taitas sang in disorder, according to their inspiration, and for a period of approximately one hour. Then came a phase of silence, sometimes they resumed their talks in a pleasant way, until they began a new cycle of ikaros. In the morning the usual healings came. Don Humberto, with reverence and humility, went to talk to Querubin Queta to request that he cure me. He agreed and, despite the cold, I had to put on my bare torso so he could clean me with songs and passes of his old man's hands on my back and arms.

Querubin Queta was about 96 years old and spent a whole night curing and healing. Let him be with the cherubs seeing the face of God.

Jacques Mabit, February 2024.

1 The title Taita (Father) refers to a person who has achieved a high degree of mastery of medical and spiritual care in the practices of traditional Amazonian medicine. He is a healer and spiritual teacher. He can face the challenges of ayahuasca sessions alone. He has the role of initiator and teacher.